The night of October 9, 2025, held a strange restlessness in the air of Kabul, Afghanistan. Suddenly, a loud explosion echoed in the sky above the city—people couldn’t even tell if the sky had torn open or if the earth had trembled. Within moments, only one phrase resonated across social media—”Kabul is burning again.”

At the same time, hundreds of kilometers away from Kabul, the ground shook from even louder blasts in Afghanistan’s Paktika province, where suicide attacks claimed the lives of several innocent people. People were saying—”This is not a bomb; it’s the roar of one country’s anger crossing another’s border.”

On the morning of October 10, 2025, the smell of gunpowder hung in the air of Kabul. Screams and sirens echoed on the city’s streets—once again, Afghanistan was bleeding. But this was not just a terrorist incident—it was the explosion of hidden tensions that had been smoldering on both sides of the Durand Line for decades.

While explosions were rocking Kabul, on the same day, Amir Khan Muttaqi—Afghanistan’s Foreign Minister—was engaged in talks regarding peace and reconstruction with India on Indian soil. This presented a strange paradox; while Muttaqi was discussing a “stable Afghanistan” in the diplomatic corridors of Delhi, Kabul and Paktika had simultaneously become “symbols of instability.”

Even though India has not formally recognized the Taliban regime, humanitarian aid and diplomatic engagement continue, as was evident from the assistance provided after the recent earthquake. Muttaqi’s visit to India immediately followed his participation in the seventh meeting of the Moscow Format.

This visit was made possible due to the temporary international travel exemption granted by the United Nations Security Council. Muttaqi’s trip to India represents a significant step towards regional diplomatic efforts and including Afghanistan in the global dialogue.

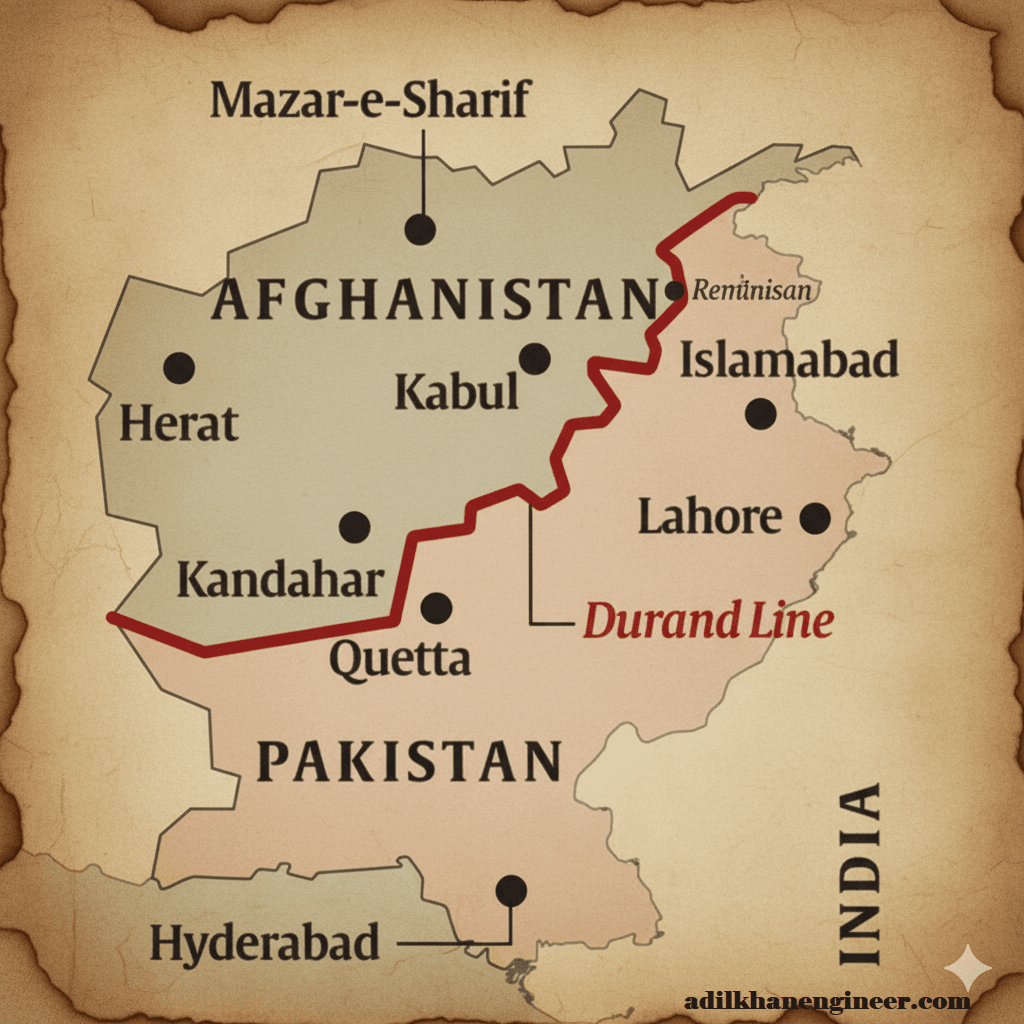

The blasts in Kabul during his India visit were not only a sign of Afghanistan’s internal insecurity but also the beginning of a new chapter in its deteriorating relations with Pakistan. The Taliban government alleged that Pakistan conducted an airstrike, while Pakistan stated, “We only targeted terrorists.” And this is where the 130-year-old wound—the “Durand Line”—was resurrected once again.

“The Curse of the Durand Line – The Story of a Burning Border”

Ancient and Medieval Context (The Beginning of the Story)

The conflict surrounding the Durand Line is not a line that suddenly appeared; its roots are buried in the soil of a civilization that has breathed there for almost 130 years. To understand this story, we must go back to an era when no line drawn on maps controlled the lives of the people here.

Imagine, This Was the Land

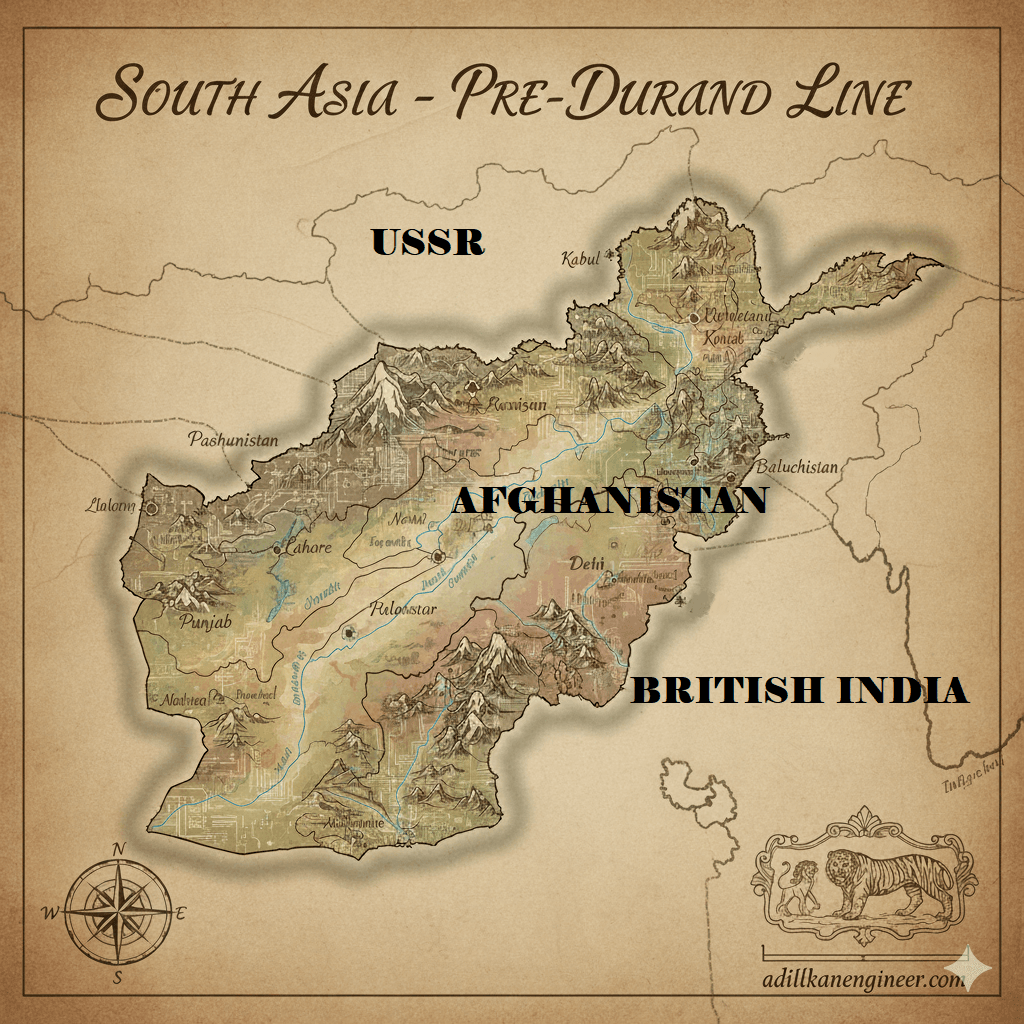

For centuries, Afghanistan and the surrounding regions have been a confluence of various civilizations. This area was the center of power for the Gurjar, Tukhar, Ghuzar, Mughal, and other powerful dynasties. But the identity of this vast region was defined less by capitals or kings and more by the people who lived here.

The soul of this land resided in its Pashtun tribes. The lives of these tribes were not governed by any government document or line drawn on a map, but were woven together by threads of blood relations, traditional customs, and centuries-old tribal loyalties.

Then the Question Arises: What Were the Borders for the Pashtuns?

For them, there was no ‘international boundary.’ Their villages, their fields, their grazing grounds for sheep and goats, and even the settlements of their relatives were traditionally determined by the friendships or rivalries of organized tribes. People of the same tribe—brothers, uncles, distant relatives—lived their lives moving freely across mountains and passes. For them, the Khyber Pass or the Bolan Pass was merely a route, not a prison wall.

This socio-ethnic fabric was so deeply woven that any future royal or colonial line was perceived by these tribes as an assault on their very existence.

And this is where the seed of conflict was sown: when, right in the middle of tribal unity and a centuries-old way of life, one day, a foreign power would arrive and say that this is ‘here’ and that is ‘there’—that line would not become a simple boundary, but a curse forever.

The British–Russian “Great Game” and the Significance of Afghanistan (19th Century)

The open world of the Pashtun tribes soon began to fall under an external shadow. This shadow was cast by the Cold War-like rivalry between two colossal empires, a rivalry that history knows as “The Great Game.”

It was a game of chess, and Afghanistan became the chessboard. On one side was the vast Russian Empire, spreading its influence southward from Central Asia, and on the other was British India, deeply anxious about the security of its “Crown Colony.”

The Role of Afghanistan – A “Buffer State”

For the British, Afghanistan was not merely a country but an essential ‘Buffer State.’ Their sole objective was to ensure that Russian forces did not reach the immediate vicinity of the British India border. Afghanistan was to act as a cushion between these two great powers, preventing the fire of conflict from reaching Indian soil directly.

This strategy proved fatal to Afghanistan’s sovereignty.

- External Interference: Both powers continuously began to interfere in Afghan politics. They attempted to change the rulers, sometimes through money, and sometimes through military pressure.

- Birth of Instability: This competition led to internal political instability within Afghanistan. Rulers became more preoccupied with pleasing external forces than their own subjects.

Indeed, when two elephants fight, the grass is certainly crushed. The fate of Afghanistan in the late 19th and early 20th centuries was similar—it was fighting for its identity and independence while two powers sought to make it a shield for their own security.

And it was to give geographical form to this ‘Buffer State’ concept that a formal, yet unnatural, boundary line was planned. The sole purpose of this plan was not to break up tribal unity, but to keep Russian influence far away.

This is where the foundation of the Durand Line was laid, which was soon to become much more than a political demarcation—it was destined to become a symbol of permanent conflict.

The Durand Line — 1893: The Line That Became a Dispute

The players of the ‘Great Game’ now decided to place a crushing seal on Afghanistan. This seal was a line on paper, which came to be known as the Durand Line.

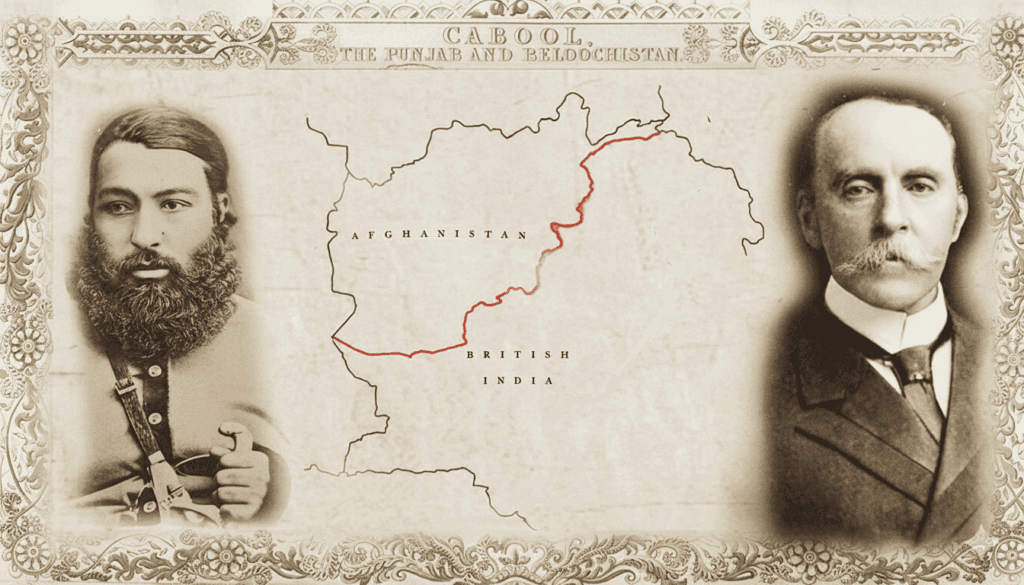

Who and When?

This ‘agreement’ took place in 1893, but it was not a pact between two equally sovereign powers. It was signed between Sir Mortimer Durand, representing the British authority, and Amir Abdur Rahman Khan, the then-ruler of Afghanistan.

The Pen Moved and Tribes Were Divided

This line, approximately 2,640 kilometers long, was drawn as the “Sphere of Influence” between British India and Afghanistan. The British objective was clear: to keep Russian influence at bay and to create a distinct boundary, even if it was unnatural.

But when this pen on paper was moved across mountains and passes, it didn’t just change maps—it sliced the centuries-old unified Pashtun tribes into two halves right down the middle.

- The Pain of Partition: People from the same family, who had shared the soil of the same fields for centuries, now became citizens of two different “countries”—some on the British India side, and some on the Afghanistan side.

- Cultural Dissection: Their Tribal Rights, language, and culture were separated. This division was artificial, and the people living on the ground never accepted it.

The Root of the Dispute: A Temporary Line?

Amir Abdur Rahman Khan reportedly signed this agreement under British pressure. Subsequent leadership in Afghanistan has always maintained that this agreement was not meant for permanent boundary demarcation.

This line, which was drawn 130 years ago for external intervention, is still not fully recognized by Afghanistan as a legal international border.

This is why, whenever tensions rise at the border (as happened recently in Kabul and Paktika), efforts by the Taliban to remove the fencing erected along the Durand Line begin. This line, though merely a pawn in the ‘Great Game’ at the time, has now become the permanent and deepest root of the conflict between Afghanistan and Pakistan.

Anglo-Afghan Wars and Colonial Intervention (1839–1919)

The drawing of the Durand Line was not the end of the conflict, but the beginning of a new chapter. This line, which divided the Pashtuns, was merely a paper solution for the British. To maintain control over the region, they continued to use force.

This Era Was Written in Blood

There were several direct and bloody clashes between British and Afghan forces on Afghan soil. These included:

First Anglo-Afghan War (1839–1842)

The First Anglo-Afghan War (1839–1842) occurred when Britain intervened in Afghanistan to counter the growing influence of Russia. The British removed Amir Dost Mohammad Khan and installed Shah Shuja Durrani, but Afghan tribes soon rebelled. The nearly total annihilation of the retreating British army from Kabul in 1842 marked a crushing defeat for the British.

Second Anglo-Afghan War (1878–1880)

The Second Anglo-Afghan War (1878–1880) began when Russia attempted to increase its influence in Afghanistan. The British defeated Amir Sher Ali Khan and forced his successor, Yaqub Khan, to sign the Treaty of Gandamak, which gave the British control over Afghan foreign policy. However, this intervention further fueled anti-British sentiment and the spirit of independence among the Afghans.

Third Anglo-Afghan War (1919)

The Third Anglo-Afghan War (1919) was fought under the leadership of Amanullah Khan, who declared complete freedom from British domination. This conflict took place on the border of British India and eventually ended through the Treaty of Rawalpindi. This treaty granted Afghanistan full independence for the first time, allowing it to emerge as a sovereign nation.

Independence… But at What Cost?

After the third war, in 1919, Afghanistan achieved limited independence. They gained some control over their external affairs, but foreign influence never completely disappeared.

The British colonial policy throughout this period revolved around one axis: Draw boundaries and control provinces. The Durand Line was the most concrete and fatal evidence of this policy.

The British never relinquished this line because, for them, it was not only a weapon to defend against the Russian threat but also a tool to keep local tribes divided and thus weakened.

In this way, by 1919, the Durand Line had become much more than a temporary administrative demarcation—it had become a symbol of colonial power. The ball was now in Afghanistan’s court to decide whether to treat this line as a permanent prison wall or an unacceptable legacy.

In the coming decades, when the winds of regime change blew across the Indian subcontinent, the burden of this unaccepted legacy was about to fall upon a new country—Pakistan.

1947: The Partition of British India and the Rise of Pakistan — A New Dimension to the Problem (AFG vs PAK)

When the sun set on the British Empire, they left behind all the problems they had created on the same soil. In 1947, the Indian subcontinent was partitioned, and a new country, Pakistan, came into existence. With this, the destiny of the Durand Line was forever changed.

When British India was partitioned and Pakistan emerged as a new nation, the Durand Line suddenly became the border between two independent Islamic countries—Afghanistan and Pakistan. But for Afghanistan, this change was not just a political event, but the continuation of a historical injustice.

Afghanistan had never considered this line legitimate, viewing it as the “imposed legacy” of the British colonial era that had split the Pashtun tribes and their cultural ties. With the Partition, the dispute re-emerged in a new form—on one side, the newly formed Pakistan insisted on the validity of its borders, while on the other, Afghanistan rejected this division.

The Burden of Legacy: The Line Inherited by Pakistan

The line that was once an ambiguous boundary between British India and Afghanistan became, overnight, the international border between Pakistan and Afghanistan. The British ‘transferred’ this disputed line to the newly formed country through a document, but this transfer was not so simple.

The Clash of Two New Perceptions

After 1947, the Durand Line became the point of conflict between two opposing national perceptions, as Afghanistan strictly refused to accept this new arrangement with the rise of Pakistan:

- For Pakistan: This line became a matter of their National Integrity and sovereignty. For Pakistan, any negotiation over this border was tantamount to slicing its own country.

- For Afghanistan: This line was an Incomplete Colonial Mark (or Scar). According to them, this division was against the will of the Pashtun people and should be abolished.

Afghanistan’s First Protest

Afghanistan strictly refused to recognize the existence of Pakistan and its inherited border. On the international stage, Afghanistan was the first and only country to oppose Pakistan’s membership in the United Nations in 1947. This protest was not merely formal—it symbolized the historical outrage stemming from the legacy of the Durand Line.

Afghanistan argued that the border was a “line of colonial oppression,” and there was no justification for its automatic validation after the Partition. This step not only laid the foundation for initial distrust between the two nations but also bound Afghan-Pakistani relations for the decades to come in a web of political, social, and military conflicts.

Thus, a colonial line, created for the ‘Great Game,’ now became the symbol of a deep-seated enmity between two independent neighbors. The story of this conflict, which extends to the recent shelling in Kabul and Paktika, is directly linked to this 1947 dispute.

1950–1970: Border Skirmishes, Political Support, and the ‘Pashtunistan’ Slogan

The Partition took place in 1947, but the fire ignited by the Durand Line did not subside. This was the era when the border dispute was no longer just a line drawn on a map, but became a serious political and ethnic slogan.

A New Front in the Name of Pashtuns

During this period, Afghanistan gave its historical objection a political shape, which was termed the ‘Pashtunistan’ issue.

- The Slogan: Afghan governments openly demanded separate rights, and even a separate Pashtun nation, for the Pashtuns living inside Pakistan.

- The Goal: This was a direct challenge to Pakistan’s National Integrity. Afghanistan believed that the Pashtuns, who lived on both sides of the Durand Line, should have the right to self-determination.

A Story of Bitterness

This political support resulted in consequences on the ground:

- Border Skirmishes: Small-scale clashes and military standoffs became common along the Durand Line between the two countries. These skirmishes often occurred when Pakistan tried to fence the border or strengthen its control.

- Diplomatic Acrimony: Relations between the two capitals, Kabul and Islamabad, remained perpetually strained. Making strong statements against each other and expelling diplomats was routine.

During this period, the anti-Pakistan stance in Afghan policy deepened, and for Pakistan, it became a permanent security concern along the Durand Line. Afghanistan kept Pakistan engaged by supporting Pashtunistan, and Pakistan reacted strongly to this.

This was the backdrop that set the stage for the geopolitical upheaval of the coming decades. The dispute had become an unbridgeable chasm. But little did anyone know that soon, the roar of Soviet tanks would echo in this chasm (as we will read next), and the relations between the two countries would change completely.

The Soviet-Afghan War and Pakistan’s Decisive Role (1979–1989)

In the late 1970s, the conflict over the Durand Line suddenly ceased to be merely regional and became global. In 1979, the Soviet Union invaded Afghanistan—and it was from this point that Pakistan’s role escalated from a border neighbor to a decisive player.

The Game of Chess Begins Again

The Game of Chess Begins Again

This was another, far more dangerous phase of the ‘Great Game.’ The old rivalry between the United States and the Soviet Union was now being fought on Afghan soil. In this game, Pakistan sided with Western powers (especially the US and Saudi Arabia).

- Pakistan’s Role: Pakistan now became the Frontline State for Western countries in the effort to defeat the Soviet Union. It openly supported the Mujahideen fighters who were battling the Afghan government.

- Strategic Aid: Pakistan provided the Mujahideen with weapons, secret training, and refuge on its soil. This support was necessary for victory against the Soviet Union, but the consequences of this were to be borne by Pakistan for decades to come.

I know you might be wondering when the Soviet Union and the Afghan government came together, the entry of the Mujahideen, and how Pakistan supported them. Let me take you back to that era.

When Did the Soviet Union and the Afghan Government Join Forces?

Yes, at that time, the USSR (Soviet Union) and the Afghan government were aligned. In fact, the Saur Revolution took place in Afghanistan in 1978, where the People’s Democratic Party of Afghanistan (PDPA)—a Communist party—seized power.

This government was pro-Soviet and began implementing socialist reforms in Afghanistan. These reforms sparked massive discontent among the Islamic society and tribal leaders (mullahs, elders), leading to an armed rebellion—these rebels later came to be known as the “Mujahideen.”

When the rebellion intensified, the Soviet army directly entered Afghanistan in 1979 to protect the Communist government (PDPA).

The war was now divided into two sides:

- One Side: The Afghan Government Army + The Soviet Union

- The Other Side: The Islamic Mujahideen (The Rebels)

Pakistan’s Role

This is where Pakistan stepped into a central role and openly supported the Mujahideen:

- Weapons, training, and funds were all channeled through the CIA (US), Saudi Arabia, and the ISI (Pakistan’s intelligence agency).

- Cities like Peshawar and Quetta inside Pakistan’s borders became bases and training camps for the Mujahideen.

- This fight was waged under the banner of “Islam vs. Communism,” attracting global Jihadi groups to join.

Outcome

- In 1989, the Soviet army was forced to leave Afghanistan, but the country descended into civil war.

- These same Mujahideen later organized as the Taliban (1994)—who were also initially supported by Pakistan.

Roots of Refugees and Militant Networks

This war permanently changed life on both sides of the border:

- Refugee Flood: Millions of Afghan refugees crossed the Durand Line into Pakistan. They placed immense pressure on Pakistan’s social, economic, and security infrastructure.

- Birth of Militancy: Arming and training the Mujahideen gave birth to a militant network that would later become the biggest internal threat to Pakistan itself—many of these groups formed the roots of the Tehreek-e-Taliban Pakistan (TTP).

This decade wove a web of blood, violence, and extremism across the Durand Line, which, even in 2025, has made life miserable and worse for the people living near the borders on both sides. Pakistan’s anti-Soviet strategy brought it international advantage but also laid the foundation for a permanent and fatal insurgent crisis on its border.

The 1990s: Civil War, the Rise of the Taliban, and the Fatal Support of a ‘Friend’

Following the Soviet withdrawal, Afghanistan did not breathe a sigh of relief but instead burned in the flames of civil war. The 1990s were a period of anarchy and a struggle for power. Different Mujahideen factions began fighting among themselves, worsening the country’s situation.

Birth of a New Player: The Taliban (1994-96)

Against this chaotic backdrop, a new and more radical religious group emerged—the Taliban. The group expanded rapidly in 1994 and seized power in Afghanistan by capturing Kabul in 1996.

Pakistan’s ‘Masterstroke’

Pakistan viewed this new player as a strategic opportunity.

- Open Support: Pakistan openly and closely supported the Taliban. Pakistan, along with Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates, were the only three countries that formally recognized the Taliban regime from 1996 to 2001.

- The Goal: Pakistan’s aim was to have a ‘friendly’ government in power in Kabul that would accept the Durand Line as the international border, keep India’s influence out of Afghanistan, and secure Pakistan’s western border.

Roots of Complications

Pakistan’s ‘close’ support seemed successful initially, but it laid a complex foundation for future conflicts:

- The Double-Edged Relationship: The same Taliban that Pakistan nurtured later refused to recognize the Durand Line, thwarting Pakistan’s strategy.

- Shift in Regional Equations: This closeness between the Taliban and Pakistan severely impacted India-Afghan relations. India did not recognize the Taliban regime, which seemingly tilted the regional power balance in Pakistan’s favour.

This was the era when Pakistan utilized its cross-border influence to the extreme. However, the ‘friend’ that was nurtured would later shelter an organization (the TTP) that currently disturbs Pakistan’s peace. Pakistan regretting this very support after the Taliban’s return in 2021 is the biggest consequence of this historic mistake.

9/11, US Invasion, and the Zenith of Bilateral Tension (2001–2021)

The events of 9/11 in 2001 changed the relationship between not just the US, but also Afghanistan and Pakistan forever. The same Taliban that Pakistan considered a strategic friend sheltered Al-Qaeda and became the target of the United States.

The US War and Pakistan’s ‘Dual Policy’

The US quickly removed the Taliban from power and established an international presence in Afghanistan. Throughout this period, Pakistan faced a strange dilemma:

- Formal Cooperation: Pakistan formally and publicly cooperated with the US, providing logistics and air space access.

- Hidden Contradiction: However, on the ground level, Pakistan’s intelligence agencies and auxiliary elements remained mired in accusations of supporting the Taliban and other insurgent groups.

This ‘Double Game’ eroded trust in Pakistan among the Afghan government and Western allies. The Afghan government and Western partners continuously accused Pakistan of providing safe haven to cross-border insurgents.

Terrorism Active on Both Sides of the Border

During these twenty years, the Durand Line became a terrorist corridor. The issue of terrorism repeatedly brought tension to Pakistan-Afghan relations:

- Rise and Challenge of the TTP: Groups like the Tehreek-e-Taliban Pakistan (TTP), whose roots lay in the militant networks of the Soviet war, began taking refuge on Afghan soil during this time to launch attacks against Pakistan.

- A Wall of Accusations: Pakistan continuously alleged that groups like the TTP were planning attacks against it from safe havens on Afghan soil. Conversely, the Afghan side refuted these charges, stating it was Pakistan’s internal security crisis.

The fencing along the Durand Line, drone attacks, and border skirmishes bore witness to the fact that the narratives of Pakistan’s security and Afghanistan’s stability were now moving in opposite directions. This tension had become a formidable wall of mistrust, setting the stage for a new and uncontrolled conflict after the Taliban’s return to power in 2021.

2017–2021: Border Fencing and the Intransigence of the ‘Iron Wall’

During the two decades from 2001 to 2021, Pakistan was constantly troubled by terrorist activities destabilizing it from across the Durand Line. To find a ‘permanent’ solution to this problem, Pakistan made a final and drastic decision: fencing the entire Durand Line.

The Wall Arose, Trust Was Broken

Pakistan began erecting a barbed wire fence along this disputed border of approximately 2,640 kilometers.

- Pakistan’s Logic (The Logic): Pakistan termed this an essential step for its national security and to curb terrorism at its root. Their argument was that it would completely stop illegal cross-border infiltration and the movement of militants.

- Afghanistan’s Opposition (The Veto): Afghan governments, whether the US-backed Ashraf Ghani regime or local tribes, declared it an illegal invasion and an occupation of historical Pashtun land.

Impact on Life—Like Severed Veins

This fence was not just a geographical line; it was cutting the veins of centuries-old tribal and family relations.

- Collapse of Local Economy: People living on both sides of the border had engaged in small-scale, traditional trade for centuries. The erection of the fence completely halted their Civilian Mobility, causing their local economy to crumble.

- Family Ties Broken: People of the same tribe, whose relatives were on both sides of the border, were now forced to undergo strict visa and checking procedures to meet them. Where once a border was crossed in one step, now an iron wall stood.

This fence gave the curse of the Durand Line a concrete, physical form. It was an act of intransigence that deepened mistrust.

When the Taliban took power in August 2021, their first symbolic action was to start tearing down this fencing along the Durand Line—a clear indication that the incomplete legacy of 1893 is still completely rejected by the Afghan leadership.

2021: US Withdrawal and the Taliban’s Return to Power — A New Era, the Old War

August 2021 marked the dramatic end of a two-decade-long war. With the sudden withdrawal of US and NATO forces, the Taliban quickly recaptured Kabul with lightning speed. This event changed the security calculus of the entire region overnight.

Hopes vs. Reality

Initially, Pakistan viewed this as a major diplomatic victory for itself. Islamabad hoped that the Taliban, which it had nurtured, would now recognize the Durand Line as the international border and expel groups like the TTP from Afghan soil. Pakistan offered cautious support and urged the international community to recognize the Taliban.

But soon, these hopes turned into a bitter reality.

‘Friend’s’ Refusal and the Rift in Relations

After coming to power, the Taliban immediately dashed Pakistan’s expectations:

- Rejection of the Durand Line: The Taliban made it clear that they would never accept this colonial line from 1893. They began removing the fencing installed along the border, which Pakistan viewed as a direct attack on its national integrity.

- Sheltering the TTP: The biggest rift occurred when, despite counter-terrorism pressure from Pakistan, the Taliban refused to dislodge the Tehreek-e-Taliban Pakistan (TTP) and other groups from Afghan soil.

Pakistan’s New Dilemma

Pakistan was now in an unprecedented situation: it was facing a government in Kabul that it had helped bring to power, but that government had now become the greatest threat to its security.

- Escalation of Accusations: Pakistan intensified its accusations against Afghanistan for sheltering the TTP and allowing them to plan attacks.

- The Taliban’s Response: The Taliban dismissed these charges, stating that the TTP was an internal issue for Pakistan.

This is the current context that gave rise to the recent conflict. The Kabul blast on October 9, 2025, the subsequent airstrikes in Paktika, and Amir Khan Muttaqi’s visit to India all illustrate that the curse of the Durand Line, even after 130 years, is writing a new and perhaps the most complex chapter of conflict.

2021–2025: TTP, Refugee Policy, and the Current Phase of Conflict (The Most Complex Era Yet)

Following the Taliban’s return in 2021, this story of betrayal entered a new and much more violent phase. Along with the old colonial demarcation (the Durand Line), the issues of terrorism and refugee policy have now brought the conflict to a head.

TTP: The Center of the Uncontrolled Crisis

Pakistan’s biggest complaint has been that the same Taliban it once considered a friend is now openly sheltering groups like the Tehreek-e-Taliban Pakistan (TTP).

Extreme Border Tension: The TTP has intensified terrorist attacks inside Pakistan using Afghan soil. Pakistan repeatedly alleges that the Afghan leadership is not taking sufficient action to eliminate the TTP, but is rather encouraging them.

Refugee Policy: Humanitarian Crisis and Political Pressure

Meanwhile, Pakistan raised the issue of the deportation/expulsion of millions of undocumented Afghan refugees.

Humanitarian Stake: Sending back these Afghans, who have lived in Pakistan for decades, not only created a humanitarian crisis but also became another tool to exert political pressure on Afghanistan. The Afghan government expressed strong displeasure over this policy, further deteriorating bilateral relations.

The Flashpoint of Conflict: Recent Events of 2025

All this tension erupted as an explosion in the events of October 9 and 15, 2025.

- Airstrikes and Retaliation: Pakistan was accused of conducting airstrikes in Kabul and Paktika, resulting in the deaths of civilians and allegedly Afghan cricketers. This attack was the extreme execution of Pakistan’s strategy to target cross-border terrorists.

- Impact of Regional Diplomacy: Amidst these attacks, Afghanistan’s Foreign Minister, Amir Khan Muttaqi, visited India. This visit raises a big question: Is Afghanistan, amidst the conflict with Pakistan, attempting to change Regional Alliances to exert diplomatic pressure on Pakistan?

Since 1947, a third name has always loomed like a shadow, either directly or indirectly, in this smoldering conflict between Afghanistan and Pakistan—a country that has always walked the path of non-violence and non-alignment, yet remained a part of this turbulent regional equation—India.

India: Non-Violence and Non-Alignment

India’s role has not been that of an aggressive power, but of a balancing nation—which attempts to safeguard its interests, the stability of its borders, and the ideals of regional peace in this complex “geopolitical quadrangle” involving Afghanistan, the Taliban, Pakistan, and China.

Amir Khan Muttaqi’s Visit to India

This story is not just about border politics, but about the diplomatic wisdom that kept India a symbol of dialogue even amidst wars. The new diplomatic page in this chapter is Amir Khan Muttaqi’s visit to India (October 9, 2025)—which has once again raised the question of whether history is repeating itself, or if the relationship between India, Afghanistan, and Pakistan is now entering a new era. We will explore the story of India, Pakistan, and Afghanistan in detail in another article, but for now, let’s focus on the challenges faced by Pakistan and Afghanistan (Taliban).

Today’s Challenges and Long-Term Impact: The Scar of Ink (Conclusion)

The story of the Durand Line, drawn in 1893, has become a narrative of blood, gunpowder, and broken trust by the time it reaches 2025. At every turn in history, this colonial line has changed its form, but its fundamental nature has remained one of conflict.

The Durand Line: More Than a Geographical Division

oday, this line is not merely a geographical division. It has become a multi-dimensional scar with several facets:

- Socio-Cultural Severance: It has torn the family and cultural fabric of the Pashtun tribes by dividing them into two nations.

- Political Rejection: No Afghan leadership, be it royal or Taliban, has been willing to accept it as an international border, which perpetually leaves Pakistan’s national integrity at stake.

- Curse of Security: This line has become the root cause of countless security issues like terrorism (TTP), the refugee crisis, and illegal infiltration.

The Current Crisis: The Burden of Historical Layers

Recent events—such as Pakistan’s airstrikes, Muttaqi’s visit to India, and the deportation of refugees—are all superimposed on this historical layer. It is clear that a permanent solution to this problem is difficult through border fencing or military operations, because this conflict resides more in the hearts of the people than on the land.

The Complex Path to Resolution

Healing this old wound will require difficult, yet necessary, steps:

- Regional Diplomacy: The solution must be sought not only through bilateral efforts but also through regional cooperation.

- Tribal Engagement: Earning the trust of the tribes on both sides of the border and prioritizing their interests.

- Sustainable Economic Alternatives: Providing lasting opportunities for employment and trade in border areas to prevent youth from turning towards extremism.

Ultimately, the Durand Line conflict shows us how a line of ink, drawn in the colonial era, continues to raise such deep questions between nationhood and humanity even in the 21st century. As long as this line is viewed as a forcibly imposed legacy, it will continue to challenge every attempt at peace between the neighboring countries.